Women’s Pension Crisis Highlights Dangers To Savers

– International Women’s Day highlights the underreported UK Women’s pension crisis

– 2.66 million affected by UK government’s change to state pension act

– Women’s pension crisis is one of many in the UK, where there is a £710bn deficit for prospective retirees

– Changes by government highlights the counterparty risks pensions are exposed to

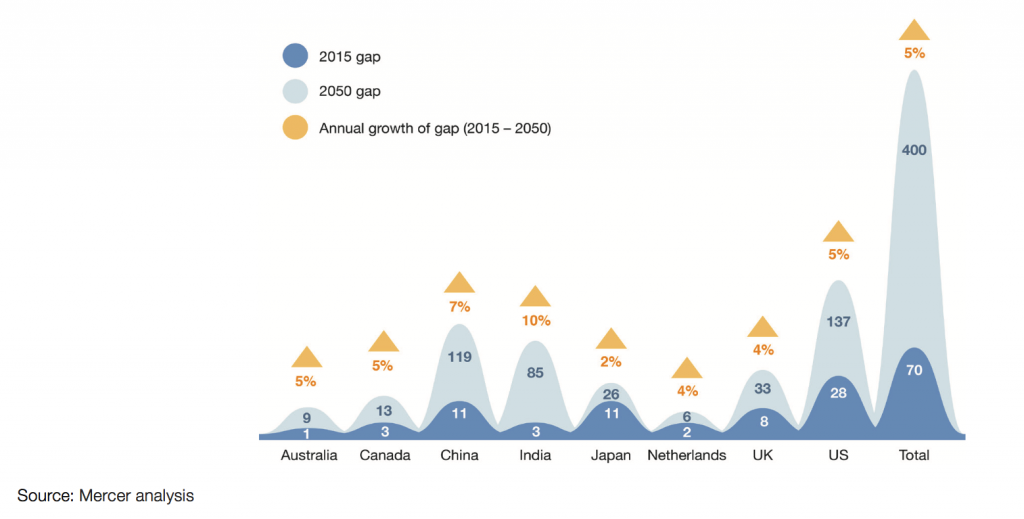

– Global problem as pensions gap of developed countries growing by $28B per day

– Savers and investors should look to invest in gold as part of their pensions

Imagine contributing to a pension throughout your working life only to be told that you won’t receive it when you expect to. When you receive this information it comes with just a few years’ notice. There is little time to make alternative pension arrangements. You have a choice: either continue to work until your pension comes in, or live on very little in the meantime.

This is a reality over 2.6 million women in the UK currently face. Those born in the 1950s have been told by the British government that their retirement ages have been increased from 60 to 65 years of age. This change means they will not receive their state pensions when they originally expected to. This is part of a move to bring men and women’s retirements to the same level.

Put that way, this looks to be a good move. Particularly when one considers the demands for women to be treated equally to men. But when a change is made in this way it is about anything but equality.

The decision by the UK government to delay paying pensions to women of a certain birthdate has resulted in one of the biggest pension crises in the UK, yet it is the least reported and discussed.

Pensions crises is something the country is rapidly getting used to. As well as the 2.6 million women affected by the UK’s Pensions Act there are the many thousands of men and women affected by private pension disasters that amount to over £710bn in deficits.

Each of these issues highlight the high exposure pensions have to counterparty risk. Millions of individuals believe they have safely contributed to a retirement pot only for the government to tell them they have to wait even longer for it or that the company they trusted to support their pension has gone bust.

UK’s pension inequality is economic inequality

Yesterday it was International Women’s Day (IWD) and on Sunday many of us around the world will be celebrating Mother’s Day. Both days are there to recognise the achievements and sacrifices of women. IWD is also there to raise attention to the plights of billions of women across the globe. Many are disadvantaged through economic, political, sexual and other means. Campaigns run throughout the year to help them but IWD is a day to really bring the spotlight to them.

Few in the West realise that IWD has an important place in the UK. We still have major problems with sex trafficking, domestic abuse and discrimination against minorities.

One of the least reported areas in the economic discrimination of women. I’m not talking about gender pay gap, the lack of female CEOs or maternity leave. In this specific instance I’m talking about the female pension crisis that has left over a two million women in a huge financial limbo.

Women Against State Pension Inequality (WASPI) explain how this has happened:

The 1995 Conservative Government’s Pension Act included plans to increase women’s SPA (State Pension Age) to 65, the same as men’s. WASPI agrees with equalisation, but does not agree with the unfair way the changes were implemented – with little or no personal notice (1995/2011 Pension Acts), faster than promised (2011 Pension Act), and no time to make alternative plans. Retirement plans have been shattered with devastating consequences.

WASPI has been campaigning for a long-time to have the changes brought in in a more economically viable manner, so that women can afford their retirements or at least have time to make alternative arrangements. They estimate those suffering as a result of the changes could be higher than the 2.6 million reported by the UK government.

In early February 2018 the government rejected WASPI’s proposals for a fairer transition period, claiming it would “represent a loss of over £70bn to the public purse.” This was a burden pensions minister Guy Opperman said he was not prepared to pass onto ‘young people’.

What about the burden of those women who have not been given enough notice regarding their retirement age? i News, spoke to one WASPI campaigner about the hardships now facing many women in their later 50s and early 60s:

“I was 58 when I got a letter saying my state pension age was going up from 65 to 66. It was a shock because I thought I was getting my state pension at 60.” Ms Eachus says some of the women she has helped have been in serious financial hardship, while others had no idea their pension age had risen. “At Christmas, we sent food and toiletry parcels to women in their sixties who are struggling. We shouldn’t have to do that. Women are having to sell their homes. One of the women I spoke to was sleeping on someone’s sofa. Some are too embarrassed to tell their family.”

In a study carried out by former pensions minister Rachel Reeves on the 2011 Act it found out of 416,000 women considered, 80,000 lost up to £8,000 because of the changes in the 2011 Act. 48,000 lost out on as much as £12,000 thanks to their new state pension age. This study did not take into account the Acts of 1995 and 2007 which stripped other 1950s born women of thousands more.

MP Frank Field, in 2006, estimated there were some women who were as much as £40,000 out of pocket, due to the changes. Those who have to continue working to the retirement age are not expected to receive more as a result of their increased economic contribution through National Insurance payments.

Economic inequality goes beyond women’s pension crisis

A report released yesterday by The Living Wage Foundation and the Fawcett Society revealed the true dangers women are economically exposed to.

A quarter of all women workers in the UK earn less than the living wage. Three out of five working women only have enough savings to last a month if they lost their job.

In short, the pension poverty of women is not set to improve. This, combined with the overall pension crisis in the UK makes for a dire future.

As of September 2017 £710 billion was the estimated, terrifying size of the UK pensions deficit. Ageing populations, low birth rates and dire monetary policy means that over 27 million people in the UK will not be receiving adequate pensions once they retire.

A 2017 report looked at both public and corporate pensions. It was the government and public pensions that were the most unhealthy, accounting for 75% of the under funding.

In November 2017, the OECD warned that the UK’s defined benefit workplace pension plans (final salary schemes) as ‘persistently underfunded’ and the state pension as seriously lacking.

It’s not much better in the corporate pensions sector of the US and UK where the WEF estimates there are over $4 trillion in liabilities.

This year the biggest pension news in the UK has come courtesy of the Carillion crisis, estimated to have left a £900 million debt pile and 30,000 pensions at risk. This was yet another example of mismanagement and lack of consideration for workers.

Everyone future retiree is exposed to these issues. They emphasise the importance of saving for retirement and ensuring your pension is both funded and properly diversified.

Men and women alike are heading for pension inequality

Here in the UK there is some growing resentment about campaigns such as IWD, many believe it is sexist. A frequently asked question on Twitter yesterday was ‘Well, when’s International Men’s Day’, suggesting men were sidelined for the female cause. International Men’s Day is November 19th and it was conceived in 1991.

In the UK (and many Western countries) there is an assumption that women’s rights campaigns have been successful and we should be happy with where we are now. The problem is that women of a certain age have been discriminated against.

For a funny reason whenever there is a pension crisis in the UK as we have seen recently with Carillion or BHS to name few, the government rallies around to find a solution. When it is a government-led crisis then they (and the media) are suspiciously quiet and unhelpful.

The pension crisis is not exclusive to women, but it is the only one that has come about due to discrimination by the government. It is a terrifying example of how the government has the power to not only provide but to also takeaway. The UK government very much holds the financial fate of these women in its hands, with very little acknowledgement of the consequences.

This example shows that when it comes to pensions that are managed by counterparties there is little control on the part of the savers. Governments and businesses have the power to decimate a lifetime of contributions in a matter of moments.

In a recent study the World Economic Forum declared a Western pension crisis. They said one of the few ways it could be managed was for individuals to ‘take responsibility to manage [their] pensions’.

It is vital that individuals take responsibility for their pensions. You must ask questions about it as soon as possible.

Particularly, you should ask if you can invest in gold as part of your pension. Internationally, the trend for doing this is extremely low which is surprising given the role it has played in preserving and growing pension wealth.

Dr. Constantin Gurdgiev, formerly an adviser to GoldCore, says the following about the importance of having gold in your pension:

“Gold is a long-term risk management asset, not a speculative one.

As such it should be analysed and treated predominantly in the context of its role as a part of a properly structured, risk-balanced and diversified portfolio spanning the full life-cycle of the investment and pension horizon for individual investors and those with pensions.

Whether they be SIPPs in the UK or IRAs in the USA.”

Gold in a SPIPP or IRA is not held hostage to a change in government policy or a CEOs reckless spending of company finances. It is there to act as a safe haven against such events.

Investors in the UK and Ireland, the US, the EU can invest in gold bullion in their pension, through self-administered pension funds.

UK investors can invest in gold bullion through their Self-Invested Personal Pensions (SIPPs), Irish investors can invest in gold in Small Self Administered Schemes (SSAS) and US investors can invest in gold in their Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs).

The pension crisis is a multi-trillion dollar/pound crisis. It is not going to go away. Adding gold to your pension is a key way to protect yourself against the economic inequality facing many future retirees.

Related reading

Pension Crisis And Deficit of £2.6 Billion At Carillion To Impact UK Pensions

UK Pensions Risk – Time to Rebalance and Allocate to Cash and Gold

UK Pensions and Debt Time Bomb: £1 Trillion Crisis Looms

News and Commentary

Stocks in Japan, South Korea surge on news of Trump-Kim meeting (MarketWatch.com)

Stocks Rise in Asia on Trump-Kim Summit; Yen Drops (Bloomberg.com)

Gold dips as dollar firms amid hopes for easing U.S.-N.Korea tensions (Reuters.com)

Stocks, Bonds Rise as Trump Signs Off on Tariffs (Bloomberg.com)

U.S. Household Debt Rose Last Quarter at Fastest Rate Since 2007 (Bloomberg.com)

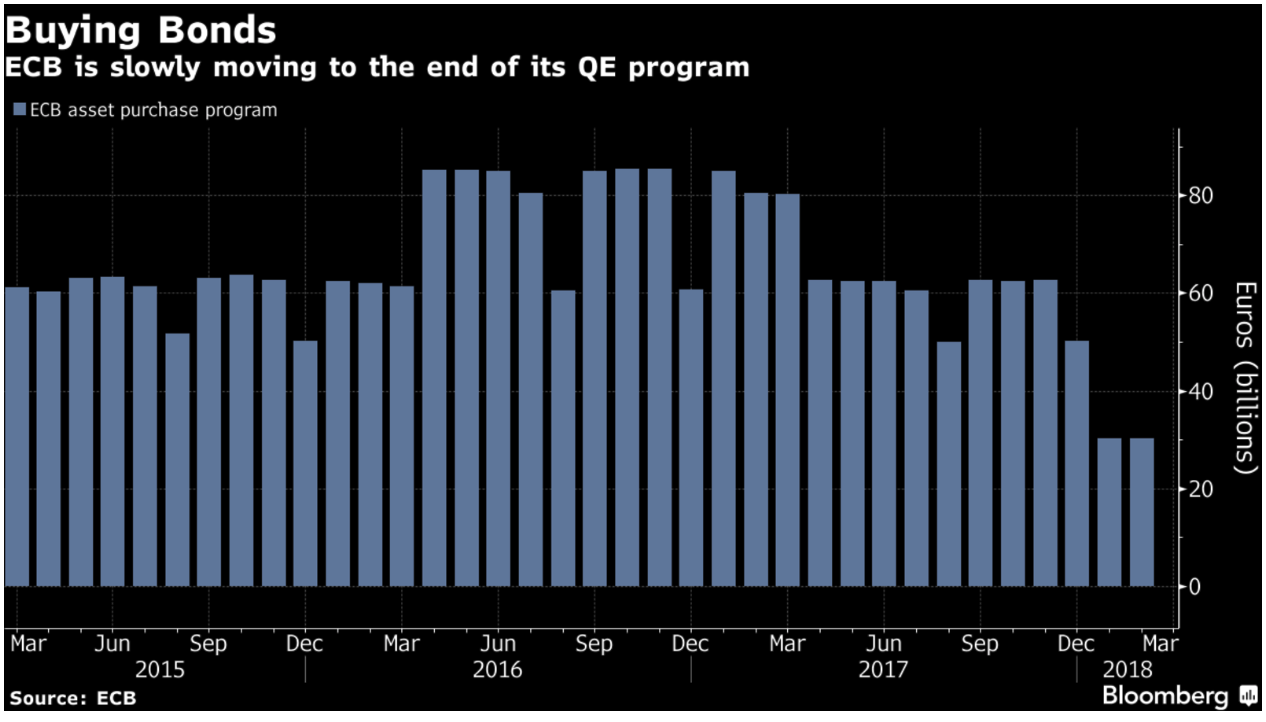

Image source: Bloomberg

Reuters exclusive: Five banks open up trillion-dollar gold club (Reuters.com)

Trump’s Historic Bet on Kim Summit Shatters Decades of Orthodoxy (Bloomberg.com)

ECB Assumes Final QE Push Totaling 30 Billion Euros (Bloomberg.com)

Hungarian National Bank Decides to Bring Gold Reserves Back Home (HungaryToday.hu)

Gold Prices (LBMA AM)

09 Mar: USD 1,319.35, GBP 955.21 & EUR 1,072.50 per ounce

08 Mar: USD 1,325.40, GBP 955.08 & EUR 1,070.39 per ounce

07 Mar: USD 1,332.50, GBP 960.07 & EUR 1,071.86 per ounce

06 Mar: USD 1,324.95, GBP 957.01 & EUR 1,074.00 per ounce

05 Mar: USD 1,326.30, GBP 958.78 & EUR 1,075.63 per ounce

02 Mar: USD 1,316.75, GBP 955.70 & EUR 1,071.04 per ounce

01 Mar: USD 1,311.25, GBP 953.80 & EUR 1,075.75 per ounce

Silver Prices (LBMA)

09 Mar: USD 16.49, GBP 11.92 & EUR 13.40 per ounce

08 Mar: USD 16.48, GBP 11.89 & EUR 13.31 per ounce

07 Mar: USD 16.65, GBP 12.01 & EUR 13.42 per ounce

06 Mar: USD 16.62, GBP 11.96 & EUR 13.41 per ounce

05 Mar: USD 16.51, GBP 11.95 & EUR 13.42 per ounce

02 Mar: USD 16.45, GBP 11.92 & EUR 13.36 per ounce

01 Mar: USD 16.32, GBP 11.87 & EUR 13.39 per ounce

Recent Market Updates

– London Property Sees Brave Bet By Norway As Foxtons Profits Plunge

– Gold Does Not Fear Interest Rate Hikes

– RaboDirect Closing – Gold May Protect From Irish Banks Going “Belly Up Again” – Finuncane

– Silver bullion will likely outperform gold bullion going forward

– Gold $10,000? Goldnomics Podcast Quotations and Transcript

– Trump Risks Trade and Currency Wars – Protectionism and Economic War Loom

– Four Key Themes To Drive Gold Prices In 2018 – World Gold Council

– Is The Gold Price Going To $10,000? (Goldnomics Podcast 3)

– Gold Corridor From Dubai to China Sought By China

– Digital Gold Provide the Benefits Of Physical Gold?

– Bitcoin or British Pound ‘Pretty Much Failed’ As Currency?

The post Women’s Pension Crisis Highlights Dangers To Savers appeared first on GoldCore Gold Bullion Dealer.

![]()

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.